This morning in Maine, I looked out my window and saw a bird in the cherry tree. It was a titmouse, a little grey bird with a yellow blush on its belly. Then, there was another; then, flickering onto a lower branch, a chickadee, then three. It was my first sighting this year of something special songbirds around here do in winter: they flock together.

A motley crew of nuthatches, creepers, titmice, and so on, coalesce into a winter flock which tumbles through the woods like a carnival. Chickadees form the nucleus of these mixed flocks because they’re quite social, alerting each other and thus the group when they find food (did you know that chickadees have regional dialects?). But researchers have found that the more diverse the flock, the better, for things like finding food or mobbing predators to defend themselves… though apparently they’re not sure yet what titmice are contributing, which is hilarious. Maybe they’re simply freeloading, but even if that’s true I think there’s something nice about freeloaders being part of the flock too.

These are backyard birds, not a “significant” sighting. But (in light of reports like this on a 73% average reduction of global wildlife populations since 1970), for me every encounter with life feels meaningful now, especially with the more-than-human world.

I’ll tell you about one.

dragonfly

The end of summer / early fall is the golden hour of the year, I think. One evening last September, in a golden hour within that golden hour, I was sitting on the edge of a pond on a farm in Vermont, a field special to me. There, I found myself eye-to-eye with a dragonfly.

Dragonflies are late summer fruit: august hunters, electric with embodied energy. They’re also territorial. That evening, as this insect darted around the edge of the pond, it frequently paused before me. Hovering over the water, impossibly still, it looked me in the eye.

It’s challenging to describe this experience in terms that don’t feel generic. It was the ringing of a bell. A tuning of attention, a moment of presence, when you come into acute awareness of the fact of being alive of this planet — how exquisite, how profound it is, to be here. In the presence of this dragonfly, I became aware that we were perceiving each other, in real time yet across the distance of millions of years of evolution towards our different ways of being. Suddenly it all came to my attention.

I often return to the way Teju Cole described moments like this to Krista Tippett, in an episode of On Being called “Sitting Together in the Dark.”

There’s the grim view of, “we’re not here for very long, and LOL no one cares.” And then there’s the other thing, which is when your favorite song gets to that part that you love, and you just feel something. Or when you’ve had a series of crappy meals and then finally, you get a well-spiced, balanced goat biryani — you know, when the spices are really fresh? Black pepper, a lot of people get black pepper wrong —really fresh black pepper. And you have this moment.

These moments of pleasure, of epiphany, of focus, of being there, in their instantaneous way can actually feel like a little nudge that’s telling you, “By the way, this is why you’re alive. And this is not going to last, but never mind that for now.” It happens in art, and it happens in friendship, and it happens in food, and it happens in sex, and it happens in a long walk, and it happens in being immersed in a body of water… and it happens in running and endorphins and all those moments that psychologists describe as “flow.”

But what is interesting about them is that they happen in real time. As Seamus Heaney says, “Useless to think you’ll park and capture it / More thoroughly. You are […] / A hurry through which known and strange things pass.”

You’re just a conduit for that. But if you are paying attention, it’s almost — I’m not sure if it’s enough, but it’s almost enough. I’m certainly glad for it. I’d rather have it than not have it.

What do you think?

Teju Cole

These moments of awareness are also, for me, painful these days because they are immediately connected to another awareness, and that is how what is simultaneously happening at enormous scale to so many beings on this planet is horrific, cruel, wasteful, and almost—actually, just too much to bear.

Moments like that bring me into contact with the awareness that life is a lineage. Each being is a candle lighting another, a flame, handing down an ancient script of the universe experiencing itself in its particular way. Passing on the light of consciousness in an unbroken line back to the mysterious beginning. Generation after generation, season after season. Glowing still.

Unless or until, in too many cases now, they extinguish.

the opposite of numbness

Years ago, I went on a walk in early spring with an Irish naturalist named Eric Masterson along the Connecticut River, which serves at the border between New Hampshire and Vermont. Eric is a birder with a particular love of broad-winged hawks. He once spent weeks cycling along with them as they flew south, because he wanted to experience migration with them.

Eric told me most people experience migration as a sudden appearance or absence at one end of the journey, not the journey itself. The return of the ospreys to the harbor, a bright flash of an oriole back at the feeder. But to see the journey, that’s hard. Migration happens mostly at night, under the stars, sometimes out over the open ocean.

I personally think bird migration is one of the great natural wonders of the world. It doesn’t get the respect that it deserves… it’s phenomenal. You have billions of animals traveling across continents every year. Billions, billions.

Eric Masterson

That this invisible there-and-back-again could be a great wonder of the world, a thing of movement enacted by billions of beings (did you know many dragonflies migrate too?), who know how to do it because of that ancient script inside their bodies and because they were taught anew by the beings alive around them, but mostly we only see the evidence that it happened.

“[They migrate] at great risk, you know. The mortality rate for these creatures is in the order of 50% for some species,” Eric told me.

There is much to survive. Birds are at risk from building strikes (I recently learned from a colleague’s reporting you can put dots on your windows to prevent this), cats, light pollution, heat waves, wildfires, people just shooting them for fun (this is truly wretched, when I read about this practice I cried and had to jump around the room shaking my body and whenever I think about it I shake and cry again), and most of all, habitat loss.

Habitat loss. Another thing that is hard to describe in ways that do not feel generic, that numb us. I think that phrase is repeated often enough that it’s hard to pay attention to the scale of it. But once you do, you see it everywhere, like this woman who is now banned from her local Market Basket because she protested the razing of a cattail marsh in the parking lot where red-winged blackbirds were actively nesting.

Flying thousands of miles takes a phenomenal amount of energy and many of these birds are so small. They need regular places of refuge, to find rest and a meal along the way. Imagine yourself after a long day of travel, how you know that at the end of it there will be dinner and a safe bed… but when you arrive there isn’t, and again the next day and again the next.

How do you see a journey?

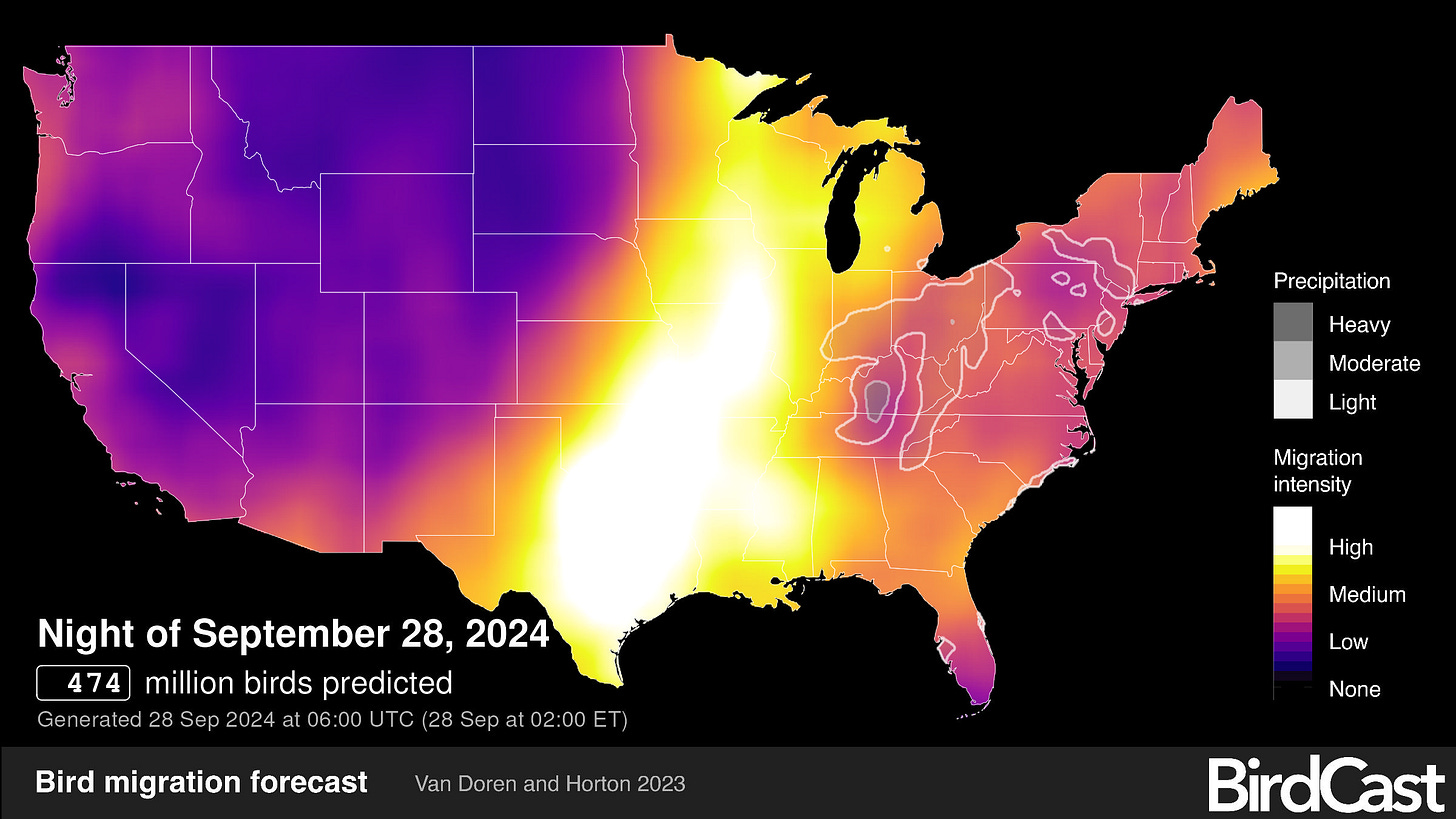

Well, you can see it on radar. Millions of birds were moving on the nights when Hurricane Helene poured into the valleys of Tennessee and western North Carolina. At the end of September, we could watch birds changing course to avoid the storm. There are so many in such concentration it’s blinding (see below, via BirdCast. Sometimes swarms of mayflies are visible on radar too).

birds are real

It’s easy to think of birding as an escape from reality. Instead, I see it as immersion in the true reality. I don’t need to know who the main characters are on social media and what everyone is saying about them, when I can instead spend an hour trying to find a rare sparrow. It’s very clear to me which of those two activities is the more ridiculous. It’s not the one with the sparrow.

Ed Yong

When journalist Ed Yong started tuning his attention to birds (in other words, he got into birding), people teased him. “Are you a retiree?” someone asked, suggesting we have time for such activities only once we’ve stopped working, stopped being productive, once we’re no longer part of the real world.

But, Ed wrote, “I reject that.”

Knowing that the night is full of birds, that those who stay stick together in diverse flocks… it creates the opposite of numbness. For me, it’s part of a reenchantment of the world.

The more attention you give to a thing, the more you see it.

I recently learned about the work of Sam Lee, a British burlesque performer turned folk singer and song collector. He gathers endangered songs held in the memories of people, often people living on the edges of what we might call mainstream society, especially members of Romany and Irish traveller communities.

He also sings with nightingales, a migratory species which sings all night long during mating season. In spring, Sam walks an audience into the dark Sussex woods, as you can see for yourself in this moonlit documentary created for Emergence Magazine by Adam Loften and Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee. There, Sam begins to sing along with the nightingale, and the nightingale changes its tune to sing in key with him.

This act, collaborating as a human animal with the more-than-human world, feels elemental. Ancient like a spell.

At the heart of this is an act of rebellion.

Sam Lee

England is at the northernmost point of the nightingale’s range in Europe, and its population has fallen by 90% in 50 years. So, Sam’s performances are many things: a ritual, an act of respect, of devotion, mourning, rebellion. A doorway in to love the nightingale.

“We can’t lament the loss of the nightingale if we don’t know what nightingale is, who nightingale is,” says Sam.

That’s a sentiment which I think certainly would have been shared by another Englishman devoted to another migratory bird: the peregrine falcon.

In The Peregrine, J.A. Baker writes about the decade when he followed a falcon. To observe the bird so closely, Baker had to let the bird come to know him too, to “wear the same clothes, travel by the same way, perform actions in the same order” so as to not scare it off. This was in the 1960s, a time when the peregrines were nearly annihilated in England from the use of DDT. So, in observing this bird for ten years, and then writing about it, Baker too was engaged in an act of rebellion.

Before it is too late, I have tried to recapture the extraordinary beauty of this bird and to convey the wonder of the land he lived in… It is a dying world, like Mars, but glowing still.

J.A. Baker

In New Delhi, India, brothers Nadeem Shehzad and Mohammad Saud care for black kites, a migratory bird of prey. It started when they were children, when their local vet wouldn’t care for an injured kite they’d found. So, they learned how to care for the birds themselves, even learning to operate on broken wings in the dark basement of their house. You can see this for yourself in the absolutely spell-binding documentary All That Breathes (I can’t emphasize enough how gorgeous and inspiring this film is).

The kites literally fall from the sky because of air pollution in New Delhi, and because they cut themselves on the strings of the other kites (the toys) flown there, which are often coated with shards of glass to cut neighboring kitestrings.

I notice in each these efforts that, in addition to the thought and intention involved, they are also physical, bodily, out in the world. They sing in the woods, set the broken wing, walk the familiar trail. Human animals caring for the more-than-human world.

It may be that these constitute fighting the long defeat, as Paul Farmer put it. But as for Nadeem and Saud, they have so far tended to more than 20,000 birds, and a huge number out of that dark basement.

Once again, I find it hard to express how profoundly I respect these sustained acts of devotion.

there are forces at work in this world besides that of evil

A major difficulty with observation and rebellion is the thing that comes along with awareness: again, for me and many, it is hand-in-hand with grief. I don’t have much to offer on this, I just know it’s our task. As a friend of mine said to me, during one of the many hard collective moments this year, “we all have to bear the Ring today.”

Speaking of the Ring…

Wildlife biologist Matt Howard recently used the example of Gollum in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings to tell the story of a sea otter ecosystem restoration project in Monterey Bay, California. It’s worth watching the full 5 minute video (“How could I possibly compare one of the world’s most adorable animals, the very ones who fall asleep holding hands so they don’t drift apart from one another, with Tolkien’s portrayal of a Reddit incel?”) but this moment is relevant to us now:

“Sometimes when we wake up and turn on these apps, all we see is catastrophe. It seems like there’s no hope. But everyday if you’re looking in the right places, you see there are people who hope anyway, and a lot of the time what they’re doing is: working.”

Matt Howard

They’re working because they hope, they hope because they work. And because they’re working, because of their acts of rebellion and mourning and devotion and protection, even if what they’re doing is fighting the long defeat, because of the working, because of them (because of you), “there are forces at work in this world besides that of evil” (per Gandalf).

In the accounts of people who lived through impossibly brutal situations, the kind where survival was not promised or even likely, it is striking how often their survival depended not on their wits or strength or whatever, but on luck. They turned one way instead of another. They found a place to hide and they stayed hidden, or they left a hiding place just in time. Someone gave them a drink in a moment when they desperately needed it.

In this crushing planetary moment, I feel like most every wild thing on this planet is going through something like that right now. A narrowing band of possibility. Migration shows us how distant forests are connected, the birds in the Maine summer woods are the same individuals flickering in the trees in Colombia and Peru. For this living wonder of the world to occur, not only do both habitats at each end of the journey need to exist, but a chain of refuges along the way must endure as well. One refuge alone cannot do much without the others, but a place to rest at the right time can make all the difference. And things like the saltmarsh still being there, or a small patch of shade, or a meadow instead of a lawn, I do think, I hope, that these things matter, in the sense that if they make a difference to the survival of any one sparrow at a specific place at a specific time, it also means it makes a difference to the Ur-Sparrow. To Sparrow. Because each is a candle which can light another, if it survives to do it.

In stories of survival, perhaps it’s not actually luck that’s striking. It’s that respite appeared. Hiding place, shade, saltmarsh, an act of rebellion: they are hands shielding a flame. It gives a chance for the flame to light the next candle. It must come while the candle is still burning, in real time.

Does that make sense? It is what I have been thinking.

I feel grateful for the many many people and other beings, close by and around the world, now and across history, for those hands. For opposing the forces of destruction, for focus, conscience, courage, and action, in the many forms that takes. For creating refuges where they can. I mentioned only a few today.

This is one of the most saving things I know. Look at all these people with their shoulders against the door of oblivion. I hold the awareness of that grand community close.

xo

Justine

what i’ve been making lately

Last year in Belgium, I met the wonderful, bright journalist Katz Laszlo. Katz later invited me to edit her series on “big oat milk” for The Europeans podcast, which was great fun and got mentions in The Guardian and Vice.

For Outside/In and NPR, I reported on the Oregon dunes which inspired “Dune,” a paradoxical little puzzle of a story involving towns buried in sand, tree islands, a coastal marten. I also talked to some of the people who, at long last, deciphered ancient Greek papyrus scrolls burned by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius 2000 years ago, and explored the meteoric rise in satellites in near-Earth space, largely due to Starlink.

briefly

I’d like to offer one immediate way to create refuge: if it’s in your power, leave the leaves instead of raking them this fall for the sake of insects like fireflies, carbon sequestration, and soil health. If that’s too much, consider a cute “bug snug” as an alternative.

A BBC4 radio story about Mudar Salimeh, a man who searches for butterflies in the mountains of Syria, by the ever excellent Falling Tree.

Listening to live music is another thing which creates the opposite of numbness. Last week in Brooklyn, I went to a show at Barbès of 14 century Sufi music performed by Falsa. Their music has been described as a “cure for alienation” and that’s how it felt to me too.

Very late to Dead Eyes but if you’re looking for a laugh and a great binge-listen, this podcast is a good one.

“Journalism can be a caretaking profession, even if it is never really thought about in those terms. It is often framed in terms of antagonism. Speaking truth to power turns into being hard-nosed and removed from our subject matter, which so easily turns into ‘be an asshole and do whatever you like.’ This is a viewpoint that I reject. My pillars are empathy, curiosity, and kindness, and much else flows from that.” (Am I fated to share just about everything Ed Yong does? Signs point to yes.)

The mutual aid networks in North Carolina right now are truly something to behold. Just look at these Google docs, shared by my friend Melanie Risch in Burnsville, NC. Melanie is also sharing lots of information and GoFundMe links to her Instagram stories in support of people who lost everything during Helene.

I’m excited about the “climate party” that Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is throwing this fall, including her speaking tour, new book, and new podcast. Wow, she is so smart and so busy.

I don’t think this conversation is a perfect one but I did learn a great deal from Ezra Klein and David Remnick talking this month about Israel and Palestine, particularly about the history of Hamas and how no one in Israeli politics is talking about a two-state solution. I also appreciated Arundhati Roy on the subject in her acceptance speech for a PEN prize.

The seed of this newsletter first emerged on Instagram, where I am more active more often. For those of you who are there too, thanks for bearing with me as I teased out the feeling in two places.